Making physics accessible

Education and Outreach team brings complex physics concepts to a K-12 level

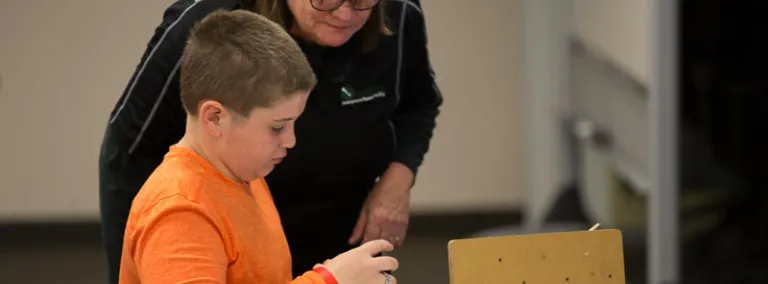

Are you smarter than a physicist? Fortunately, you don't have to be. At Sanford Underground Research Facility (Sanford Lab), our experienced team of education specialists make complex physics concepts accessible to everyone, especially K-12 students and teachers. With nearly 100 years of experience in the fields of STEM education among them, the Education and Outreach Department (E&O) translates particle physics experiments, geothermal energy exploration and extremophile biology into a language that is easy to understand—right down to the kindergarten classroom.

“Besides assembly programs and field trips, we also provide K-12 curriculum modules for educators to implement in their classrooms,” said Peggy Norris, deputy director for E&O. “We work very hard to make the educator comfortable with the material and to make it understandable to the students.”

But how, we asked, do you make the complex science explored at Sanford Lab, such as particle acceleration at CASPAR (Compact Accelerator System for Performing Astrophysical Research), accessible to fifth graders?

Learning through inquiry

“You always start by asking questions,” Norris said.

Modern curriculum development, Norris explained, is driven by student questions. The goal is to let the curiosity and problem-solving of students propel the conversation. To facilitate this, educators try to imagine the type of questions students will have about a topic, then build the lesson around those questions.

“We are trying to develop a storyline,” Norris said. “By thinking like a student, we can help them discover the answers themselves.”

Getting it right

To develop new curriculum modules, our educators start by asking questions of their own.

“In order to create an activity based on particle acceleration, I spent a lot of time with the researchers at CASPAR. I needed to understand—to visualize—how these concepts could be translated into a fifth-grade classroom,” Norris explained. “Once I had a good grasp of the science myself, I created the activity, then let the scientists review my materials, just to make sure I had it right.”

After the lessons have been fully fleshed out, fact-checked by scientists and reviewed by educators, they hit the real test—a classroom.

“We offer professional development instruction to educators, covering best practices and getting them comfortable teaching the material,” Norris said. Once the material is introduced in classrooms, educators give feedback to the E&O team, allowing student-questions to reshape lessons.

At the end of some lessons, students even get to take their questions straight to the source through a video conference with real-life scientists at Sanford Lab.

Putting it all together

In addition to formulating lessons around student questioning, our educators always incorporate a hands-on element to engage students.

Take the particle accelerator activity, for example. Each student receives a plastic cup with a marble inside. The first question posed to students is this: “How can you get the marble to spin around the cup as fast as possible?”

“They will spin around, twirl the cup, have it right-side-up and up-side-down—all kinds of things to get it moving quickly,” Norris said with a smile. After students try this out, they are faced with a new question: What if you had to do this 24 hours a day? Can you think of a mechanical way to keep it moving?

“Usually they will come up with robot arms,” said Norris. “Some will discover that they only need to move the cup back and forth, so they will come up with a vibrating table.”

Finally, the educator asks: What if the marble was magnetic? Is there something else you could do? This is when the concept of a particle accelerator is introduced. With a bit of imagination, the cup becomes a particle accelerator—like the 50-foot CASPAR accelerator or CERN’s 17-mile-circumference Large Hadron Collider, depending on the size of your imagination—and the marble becomes a particle. Educators explain that the accelerators use magnets to steer and focus invisible particles at a target, creating a very specific reaction they want to study.

“We always tie concepts back to Sanford Lab, because it’s important for students to know that big things are happening close by, in their state or region,” said Norris. At Sanford Lab, scientists are doing the same thing—question-driven exploration of the universe. “It’s an ongoing hunt here, and we want students to see that they can contribute to these big issues too, as long as they keep asking questions.”