Roggenthen’s rocks: decades of study and advocacy for geosciences at SURF

Dr. Bill Roggenthen, a professor emeritus of geology at South Dakota Mines, has been reading the rocks at America’s Underground Lab since the 1970s.

The 370 miles of tunnels and shafts that make up the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF) are cut into a remarkably complex set of rock formations.

For geologists, these rocks are like pages in a book. They tell the incredible story of the deep history of our planet. Some pages describe underwater hot springs that once spewed bubbling fluids, rich in minerals, across an ancient ocean floor. Some pages tell the story of early photosynthesizing plants on the planet and the revolution of oxygen breathing life they pioneered. There are entire chapters on plate tectonics, where layers of rock are contorted into mighty mountain peaks—only to be humbled by eons of time—as they erode back into the sea.

Bill Roggenthen began reading this book in the 1970s; he has yet to put it down.

Roggenthen is a professor emeritus of geology at South Dakota Mines. As a young faculty member he spent time inside the Homestake Mine with students and miners delving into the geology of the site. After the gold mine closed in the early 2000s and as the idea of America’s Underground Lab began to take root, Roggenthen played an integral role in making the case for the facility that SURF has become today.

He took part in an early meeting in the town of Lead in 2001 on the proposal to turn the former mine into a laboratory space. This meeting was followed up with gatherings at Lawerence Berkeley National Lab in California and at the nation’s capital, Washington, D.C., that helped lay the foundation for the potential for geosciences in underground laboratories.

Earth Lab: a vision come true

“The publication that we put together for the National Science Foundation, was called Earth Lab, and it's still available,” Roggenthen said. “It lays out what might be done in terms of geology, biology, geophysics, in an underground laboratory. It came out in 2003, and that's how things kind of got going here at SURF.”

Roggenthen went on to work alongside others in the Black Hills as the co-principal investigator for the Deep Underground Science and Engineering Laboratory (DUSEL) that was a precursor to SURF. He says some of the vision that helped form SURF more than 20 years ago, is coming true today.

“A lot of the early things that were discussed in Earth Lab and DUSEL have been coming about. There is a strong biology presence, which was talked about in Earth Lab. There are various seismic experiments that have been done and are being done that were talked about in Earth Lab. Earth Lab explored the potential for studies of rock mechanics and part of this has been done or is underway with more potential for the future,” Roggenthen said.

Rocks Mechanics: understanding what bends and breaks

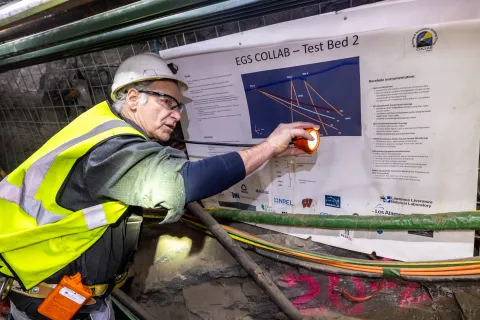

Dr. Bill Roggenthen, a professor emeritus of geology at South Dakota Mines, speaks inside the geothermal laboratory, 4100 feet below the surface at SURF.

Photo by Matthew Kapust

Students of structural geology learn that with enough heat and pressure, anything will bend. The intricate folds found in the layers of solid rock exposed underground at SURF are an excellent example of this principal. For Roggenthen, SURF also provides a fantastic test bed to better understand the deformation of rocks in real time.

“At SURF we can study the dynamic properties of how rocks deform, because that's what they're doing right now,” he said. “For example, on the 4100 level of SURF we can see rocks that are currently deforming. Studying this process is important for underground construction. In the future, we may see an increase in deeper underground construction. As perhaps, cities get more crowded, we'll see more and more taking advantage of the subsurface.”

Research in rock mechanics is tied closely to research in how fractured rocks can enable the extraction of geothermal energy. In the past ten years, SURF has played an important role of the effort to create new forms of energy sourced from the heat deep inside the earth.

Enhanced Geothermal: an untapped energy revolution

Roggenthen has been a key player in research on Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) at SURF. These systems could revolutionize the production of electricity by allowing the construction of geothermal power plants almost anywhere on the planet.

Roggenthen joined the (Permeability (k) and Induced Seismicity Management for Energy Technology) kISMET collaboration, that started in 2014, on work to characterize the state of stress of rock exposed on the 4850 Level of SURF. He went on to take part in the EGS Collab project that helped test and verify computational models inside a geothermal test bed at SURF. Today, Roggenthen remains involved in the ongoing research in the Center for Understanding Subsurface Signals and Permeability (CUSSP) experiment that is further paving the way for expanded geothermal energy in the United States.

“Building the understanding of how to make and maintain fractures that create intimate relationships between the fluid you're putting down and the heat that you're trying to extract, that's a key to the whole business,” Roggenthen said. “If you do that, then you can have geothermal energy just about any place.”

Advancing revolutionary breakthroughs in areas of science like geothermal energy production is a key part of why SURF was established two decades ago.

The potential for future geoscience research at SURF, in areas from geothermal energy to seismic studies and rock mechanics, show that the stories told by the layers of rock beneath Lead, South Dakota are far from over. Geologists have been reading these rocks since mining started here almost 150 years ago, and those like Roggenthen will be glued to these pages for decades to come.